The birds come in waves as if pushed by a strong wind–cardinals, robins, bright yellow goldfinches, wrens with tails sticking up. We even have a woodpecker with a red head and white and black stripes running down its back. They descend fast and stay in the bird feeder for a long time. I stand in the kitchen window with the morning coffee in my hands and watch them–their graceful yet fast movement, the folding of their wings, the taking off. I see some bossy pants among them–they move faster than the others and claim more space.

I live in Woodland Park in Ellicott City–one of the most beautiful places on the planet. My house sits on a hill that falls sharply down to the stream that sometimes swells with rain. The hill–running along the side and the back of my house–is graced with old and new trees. Except for winter, the trees form a dense wall, separating us from the world. Every time I look out the window, I see trees. Their solid trunks and branches keep me grounded. The trees are home for the birds that come to my bird feeder.

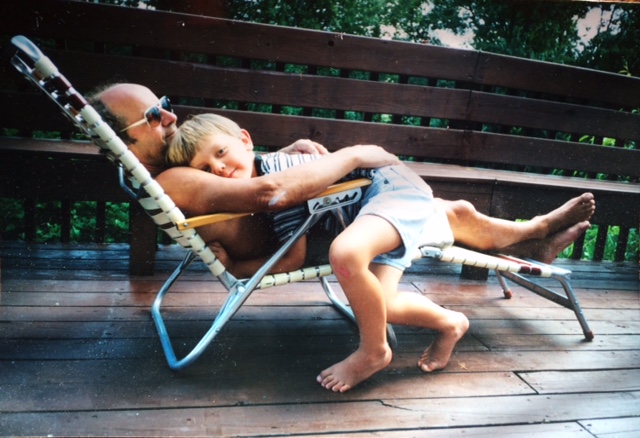

The bird feeder needs painting, I think to myself. It looks old and dilapidated. I know the birds don’t mind, but let’s face it–it’s been a long time when my father built it for Alex. It was a beautiful summer, and the two of them were inseparable. They built the bird feeder, a solid book shelf that fits perfectly in my living room, turned all the boards on the deck upside down and painted them with fresh stain.

I stand in the kitchen window and recall the time when my father came to visit. It was after my mother’s passing. He was thin like a rail. His dark eyes looked at me with sadness I didn’t know before. I love you dad, I said, holding him tight. I miss her, he said, and we cried. I still remember his smell–Old Spice, coffee, and cigarettes that claimed his life in 2012.

I see the bossy pants birds again and think that it’s time to paint the bird feeder. Every year I try to convince myself that it’s a good idea. It will look nicer, and that’s a strong argument. And, it will last longer, right? I nod to myself or to the birds on the other side of the kitchen window.

The thing is. The thing is … every time I touch the bird feeder, I remember my father’s hands. His hands ran along the grain of the wood I see today. His fingers smoothed the surface with a piece of rough sandpaper. Sometimes I run my fingers on the wood as if tracing the places he touched. With my index finger I poke the heads of the nails. I touch the shingles he placed on the slanted roof. Why do I do it? To remember? To have the places he touched still “visible” (and not painted over)? I don’t know.

Where is the memory stored? Is it stored is the object, in the bird feeder? Is it stored in the picture showing how my son melts into his grandfathers arms?

Maybe this year, I say to myself, maybe this year it’s time to paint the bird feeder. It looks like it’s time. Maybe.